A whole history of art history writing could profitably be written concerning the changing uses of illustrations. When an art writer does not use illustrations, as happened in Clement Greenberg’s The Nation reviews, then it’s often necessary to describe in words some of the visual works under discussion. And when, as in nineteenth-century editions of John Ruskin, his line drawings are reproduced, then there is now a certain archaic charm to these illustrations. In the early and mid twentieth century, art history writing often relied on just black-and-white illustrations, usually grouped together. In a variation on this system, some exhibition catalogues offer one group listing images of art in exhibition and another list, numbered differently, of reference illustrations. And Skira had a marvelous, posh system, tipped-in color plates held on paper hinges. Then, of course, nowadays one gets color illustrations, sometimes mixed with black-and-write images of the less critical examples. Finally, in recent art history publishing there is a tendency to place color images in the text, as near as possible to the written discussion. And, also, to provide full information about the picture’s location and dimensions to an afterword, with just identification of the artist and title set by the image. That procedure makes for a more harmonious layout.

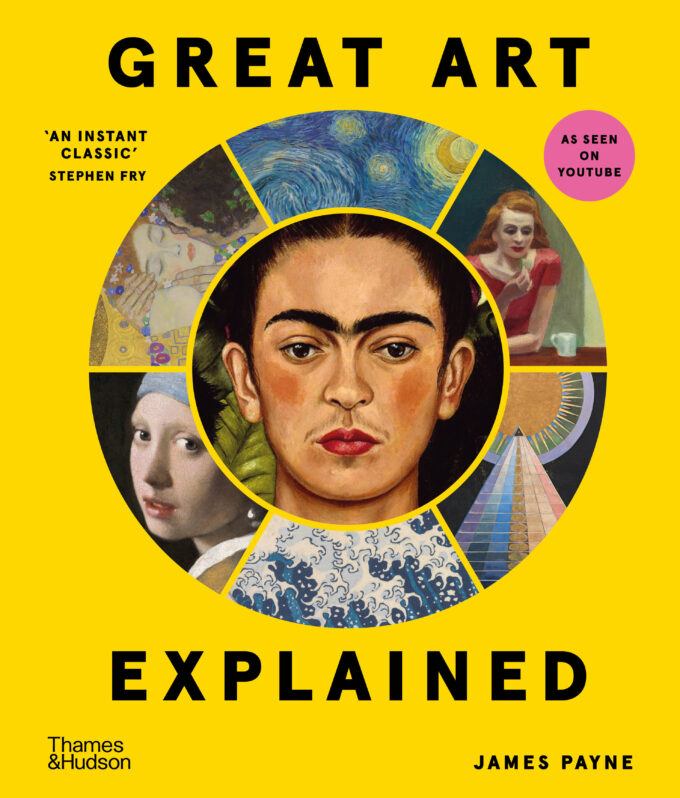

What’s in the background of these dramatic changes, of course, are complicated legal questions about pictorial rights, and, also, the evolving technologies of image production. And of course, everything is changed still again when one reads an illustrated book as a PDF, as I read James Payne’s Great Art Explained: The Stories Behind the World’s Greatest Masterpieces, produced by Thames & Hudson in 2025. With large, often two-page pictorial spreads of high-quality color images, these pictorial references effectively support the text, which is terse and happily visually oriented. A similar effect is found, I think, in online review journals like the Brooklyn Rail or Two Coats of Paint, where extensive, large illustrations can accompany a short review. There’s no need to waste words describing what you can see. What will happen to academic art history and its teaching now that so many images are so readily available? So far as I know, there is as yet no good survey account of this important concern. In my experience, as a retired teacher and still productive writer, the availability of YouTube materials changes rather drastically the experience of presenting art. In writing about old master sacred works, for example, it’s possible to check your memory of their site. And in discussing contemporary art, it’s easy to test your recollections of details. Still, however, there are important legal distinctions between these private uses of images and reproductions for publication.

Great Art Explained is a superb example of how change in various aspects of a culture are linked. Compare this book, if you will, to the grand treatise of the era of my youth, Ernst Gombrich’s The Story of Art, first published in 1950. Gombrich, proceeding in chronological order, focuses — this is a frequent complaint nowadays— almost entirely on pre-contemporary European art. The publisher has regularly updated this book, which has been translated into many languages. Still, he includes very little work from Africa, China or India—and only a small, idiosyncratic group of twentieth-century artworks. But now feminism and concern with non-white artists has really arrived in art history. Payne includes Hilma Af Klint, a Swedish artist; Suzanne Valadon, a French artist; Yayoi Kusama, a Japanese woman; and Isaac Julian, a Black English artist. And there is a self-consciously ahistorical arrangement of his great artists, for the idea of progress in picture making is no longer taken seriously. Neither is a Eurocentric canon important today. Although these great works are arranged in historical order, a presentation in which an eleventh-century Chinese cityscape is followed by a portrait by Jan van Eyck, or, later, we get in succession works by Salvador Dali, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Faith Ringgold shows that traditional ways of plotting art’s history are no longer convincing. Nor, I would add, can we appeal to conventional ideas of visual quality, or the canon.

The effect of Payne’s layout is rather like walking through an ambitious museum, like MoMA in its recent incarnation if you will, in which visual examples are accompanied by a gifted narrator who provides a voice-over which gives information picture-by-picture, without providing a plot for the story. You sense, rather, that the great artworks are very diverse. And anyone who has read older, slightly older surveys is undoubtedly aware that this canon is likely, in turn, to be subject soon to further revisions. When Gombrich sets the classic Greek works near the start of The Story of Art, one is aware of his roots in very traditional Western ideals of visual culture. It’s revealing that Payne begins instead with Zhang Zeduan, a Chinese old master painter. What I find most masterful in Payne’s account is his uncanny ability to move swiftly from one example to the next one, in a way that builds upon the support of full large, excellent color plates. In his hands, thirty works provide an instructive perspective on world art history, as it is seen now. Soon, of course, there will be more developments.

Meanwhile, the changes within art books from Gombrich’s era to the present in the past seventy-five years are as dramatic, I think, as the changes within art itself. I know Gombrich’s writings very well, for in the 1970s I devoted a doctoral thesis in philosophy in part to him. And so I hope that now some young scholar will chart the restless movement presented in Great Art Explained. Change can be exciting!