Murasaki Shikibu composing “The Tale of Genji.” Artwork by Tosa Mitsuoki, before 1691. (Photo: Ishiyama-dera Temple, Public domain)

Many consider the Kish Tablet from Sumer to be the world’s oldest written text, dating back 5,500 years to the Uruk period (c. 3500–3200 BCE). It goes without saying that the written form has dramatically evolved since its proto-cuneiform origins, transforming into verse poems, epics, fables, and much more. Novels as we know them, however, only arrived later, wholly unique given their considerable length, fictional narratives, and use of prose rather than verse. It can, of course, be difficult to fully confirm the world’s first novel, but The Tale of Genji is widely regarded as holding that title.

Written more than 1,000 years ago during the height of the Heian period (794–1185), The Tale of Genji was penned by Murasaki Shikibu while she served as a lady-in-waiting at the Japanese court. The manuscript, whose most recent English translation spans 1,300 pages, follows the tender, charismatic Prince Genji, tracing his life and many romantic pursuits against the backdrop of 11th-century Japan.

“Murasaki Shikibu was writing in a mode of literature that was, at her time, fairly denigrated,” Melissa McCormick, a professor of Japanese art and culture at Harvard, told the BBC. “[It’s a] monumental work of literature.”

Indeed, Murasaki wrote the text in a new form of phonetic script called kana, a vernacular style often associated with women’s writing at the time. Kana also marked a stark departure from the court’s scholarly language and prestigious literature, both of which were conducted in Chinese characters, or kanji, and typically required specialized study.

“Women of the time were writing in the vernacular, so [they] were able to express themselves eloquently,” John T. Carpenter, a curator of Japanese art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, explained. “In fact, the writing system they used was called onna-de, literally meaning the ‘woman’s hand.’”

Its incorporation of kana aside, The Tale of Genji was also disparaged for being a work of fiction, a literary style that wasn’t nearly as popular or respected as it is today.

“Fiction was on the lower rung of the scales, of the genre hierarchies,” McCormick added. “But she produced such an incredible tour de force work of literature that it had to be taken seriously.”

The novel’s characters, too, offer what McCormick understands as an unprecedented sense of “interiority.”

“For the first time, you had characters that really jumped off the page,” McCormick said. “That was through a kind of writing in which you have a sense that you’re in the characters’ thoughts.”

Centuries later, these characters still “jump off the page.” For that reason, perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise that The Tale of Genji is consistently lauded as one of history’s most elegant, sensitive, and spellbinding pieces of narrative fiction.

Written more than 1,000 years ago, Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji is widely considered to be the world’s first novel as we know it.

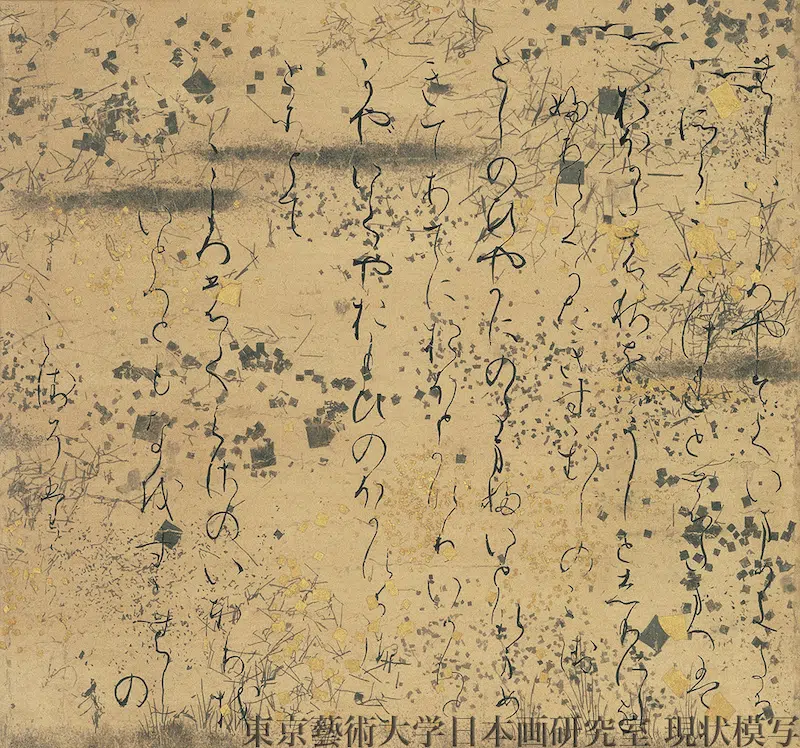

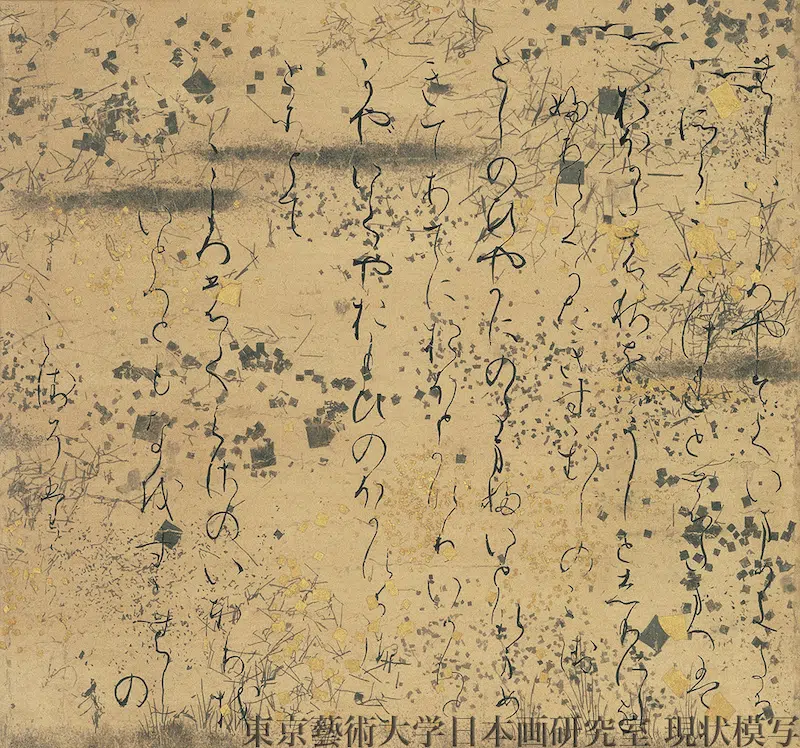

A fragment from the illuminated scroll of the “Tale of Genji.” (Photo: Gotoh Museum, Public domain)

The work was written at the height of Heian period (794-1185), and follows the life and romances of the gentle Prince Genji.

Murasaki Shikibu at Ishiyama-dera, from 1767. (Photo: Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Public domain)

The Tale of Genji is distinct in its considerable length, fictional narrative, and use of prose rather than verse, which was the preferred literary form of the time.

An illuminated scroll of the “Tale of Genji” (Photo: Gotoh Museum, Public domain)

Sources: The Tale of Genji; The Tale of Genji: The world’s first novel?; Asia For Educators: The Tale of Genji; The Tale of Genji: A Visual Journey Through the World’s First Novel

Related Articles:

Here Are Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Eight Books That “Every Intelligent Person” Should Read

Dive Into Over 10,000 Historical Children’s Books Thanks to This Fascinating Database

This Is the Only Illuminated Manuscript From Antiquity Depicting Homer’s ‘Iliad’