Japanese history is not short on great women, from fearsome female warriors to wise empresses, poets, and more. Yet one name rarely makes its way to classrooms and the Japanese consciousness: Himiko. Many historians believe that she was a real 3rd-century-CE warrior queen and shaman who used her skills of diplomacy and divination to create a kingdom in the land of Yamatai, ending a civil war. Despite that, the most famous depiction of Himiko might be the 2018 Tomb Raider movie. Let’s find out why that is.

The Female Rulers of Japan

Under the Imperial House Law of Japan, “The Imperial Throne shall be succeeded to by a male offspring in the male line belonging to the Imperial Lineage.” That is Article 1 of Chapter 1 of the regulations determining who gets to sit on the Chrysanthemum Throne. However, this rule was almost changed a few years ago since the current emperor, Naruhito, only has a daughter, Princess Aiko. A beloved public figure, there was widespread support for her and the abolition of male primogeniture but, in the end, it was decided that Emperor Naruhito will be succeeded by his brother, Crown Prince Fumihito, who does have a male heir.

Things were not always so strict in Japan. Out of 126 Japanese emperors, eight were women, including two who ruled twice under different names. The official first Japanese empress was Suiko (ruled 592-628), who oversaw the construction of Horyu-ji Temple (containing the oldest wooden building on the planet) and maintained close diplomatic ties with China. But a few centuries before her, there supposedly was another woman who ruled much of Japan. She was not an empress, though. She was more of a war chieftain and priestess who rose to the role of queen. Or so the stories (and historical sources) say.

A Veiled Footnote in Japanese Historical Sources

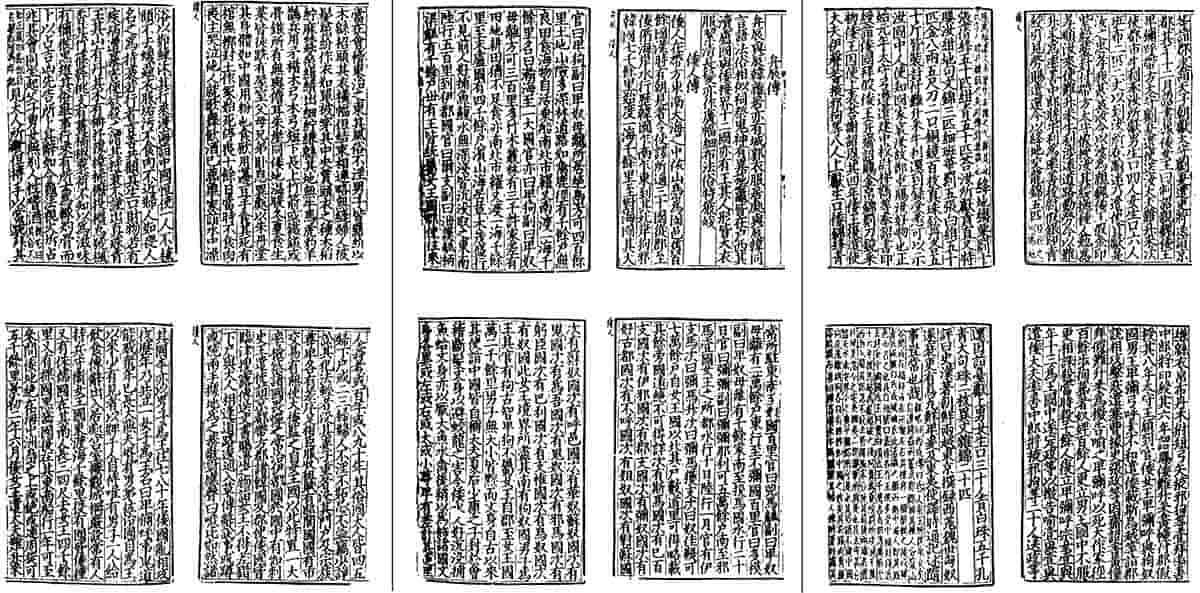

The 8th-century text Kojiki, which aimed to trace the imperial line all the way back to the goddess of the sun, Amaterasu, mentions many things, from the creation of Japanese islands to a very detailed account of the legendary first emperor, Jimmu, who almost certainly did not exist. Yet because of the Kojiki, we know what songs he sang (Yasumaro, 2014, pp. 66-68), what ambushes he avoided, what mythical creatures he used while consolidating power (a three-legged crow). The Kojiki makes no mention of Himiko but it does describe someone fitting her description.

According to historical sources, Himiko was the daughter of Emperor Suinin. Kojiki mentions that one of his wives, Hibasu-hime, gave him a daughter called Lady Yamato (Yasumaro, 2014, p. 88), a priestess of Amaterasu and keeper of the sacred sword Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi (Grass Scyther), today one of three Imperial Regalia of Japan. The Nihongi chronicle says that Yamato was also the first priestess to worship in Ise after receiving a vision from the sun goddess herself, who said: “[Ise] is a secluded and pleasant land. In this land I wish to dwell” (Aston, 2008, p. 176). This is considered the mythical origin of the Ise Grand Shrine in Mie, one of the most important places of Shinto worship in all of Japan. It is also pretty much all that Japanese texts have to say about Himiko, if Lady Yamato truly was her. Chinese sources, on the other hand, are much more detailed.

The Queen of Wa

The Records of the Three Kingdoms—composed in the 3rd century CE and covering the end of the Han dynasty—is a Chinese chronicle considered a reliable historical source and our best evidence for the existence of Himiko. The text mentions her as a shaman-queen who was elevated to royal status by a council of local chiefs in order to end a civil war in the land of Yamatai. While there are a lot of theories about where Yamatai actually was located, Ise or somewhere else around central Japan are the top contenders, as is Kyushu. Wherever it was, Himiko brought peace to Yamatai not just by force but by her diplomatic skills and claims of magical powers.

She most likely relied primarily on the former when communicating with China. The Chinese emperor recognized Himiko as Queen of the Wa, with “Wa” being the Chinese name for Japan at the time (Yoshie, 2013, 22). The emperor also sent her a gold seal, textiles, and bronze mirrors. However, this was a response to tributes first presented by Himiko’s emissaries, an act that officially recognized China as a greater power and has been interpreted as a sign of fealty. The fact that Himiko skillfully ended decades of fighting among the ancient chieftains of Japan speaks to her political acumen and suggests that she deemed a tributary relationship with China to be the smartest move for her. But it might have been what ultimately doomed her to historical obscurity.

Double Standards

No one outright says it, but sending tribute to China might have negatively influenced some Japanese historians’ views on Himiko, causing them to try and write her out of history. According to the historian Professor Akiko Yoshie, there is also a strong gender bias when it comes to research on Himiko. When she is not being erased from history or meshed together with unrelated figures like the legendary Empress Jingu, her abilities and importance are constantly being downplayed (Yoshie, 2013, pp. 7-8). Early sources that do recognize Himiko as a real figure describe her almost like a charlatan who conned her way to the role of queen by claiming that she had magical powers. This essentially robs her of her powers of persuasion, diplomatic skills, and keen political acumen, like using the legitimacy of a powerful nation like China recognizing her as queen to secure her position in Japan.

Other sources go further and describe her as a puppet who kept the population in line using their belief in her magic powers while all the real ruling and fighting was actually done by her brother. What was his name? Nobody knows. For someone who was the “true” ruler of Yamatai, the name of Himiko’s brother became lost to history, putting a damper on the theory that he was the real power behind the throne. Chinese sources mention him as assisting Himiko in administering Yamatai, but that is about it.

Assumptions like this almost never happen with male rulers who claimed to possess mystical abilities. The 7th-century Emperor Temmu, for example, was a conqueror through and through who consolidated imperial power and maintained close diplomatic relations with the Korean kingdom of Silla. He also was a priest of Amaterasu who worshiped at Ise and claimed to be able to see the future, communicate with gods, and bring down storms upon his enemies. Between his embassies, a connection to Ise, and claimed supernatural powers, Emperor Temmu almost comes off as a male version of Queen Himiko. Except that nobody has denied his existence or military accomplishments.

Burying Himiko

Empress Koken ruled in the 8th century, abdicated, then won her way back to the throne as Empress Shotoku. She is often mentioned as the reason for the (randomly enforced) ban on female rulers as she supposedly was manipulated by the monk Dokyo, whom she was said to be madly in love with. Given that history, Japanese or otherwise, is often written by men, there is some doubt about the actual motives of Koken/Shotoku, but she remains one of the first arguments that many people bring up to justify Article 1 of the Imperial House Law of Japan.

This, in turn, influences people’s perception about power structures in early Japan. When one of only eight Japanese empresses becomes the subject of a scandal based on uncontrollable emotions, it makes it harder to imagine a world where female leaders were the norm. Himiko, Suiko, Koken/Shotoku, and others were true rulers with real power and authority, not puppets or transitional figures keeping the throne warm until a suitable man came along. Prof. Yoshie has put forward a claim that archaeological excavations of burial sites prove that many ancient Japanese chieftains were female, based on the weaponry and symbols of power buried with them (Yoshie, 2013, p. 12).

The Hashihaka kofun tomb in Nara, the first large keyhole-shaped kofun in Japan—which was constructed around the time of Himiko’s reign—is suspected by some to be the queen’s resting place. There might be a hidden chamber inside it that could potentially be the location of Himiko’s remains, but access to the site has been limited by the Imperial Household Agency, who treat the kofun as a mausoleum of the imperial family.

As things stand, Himiko’s legacy remains under threat. Real or not, she deserves a place in Japanese history, which hasn’t been shy about venerating legendary rulers. Why not give Himiko the same treatment? She is a fascinating figure that combined military, spiritual, and diplomatic powers to create her own queendom in a time of constant war. That’s more than deserving of some recognition.

Bibliography

Translated by Aston, W. G. (2008). Nihongi Volume I – Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Cosimo Inc. (Original translation published 1896).

Yasumaro, O., translated by Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki, An Account of Ancient Matters. Columbia University Press.

Yoshie, A., translated by Azumi, A. T. (2013). Gendered Interpretations of Female Rule: The Case of Himiko, Ruler of Yamatai. U.S. Women’s Journal, No. 44.