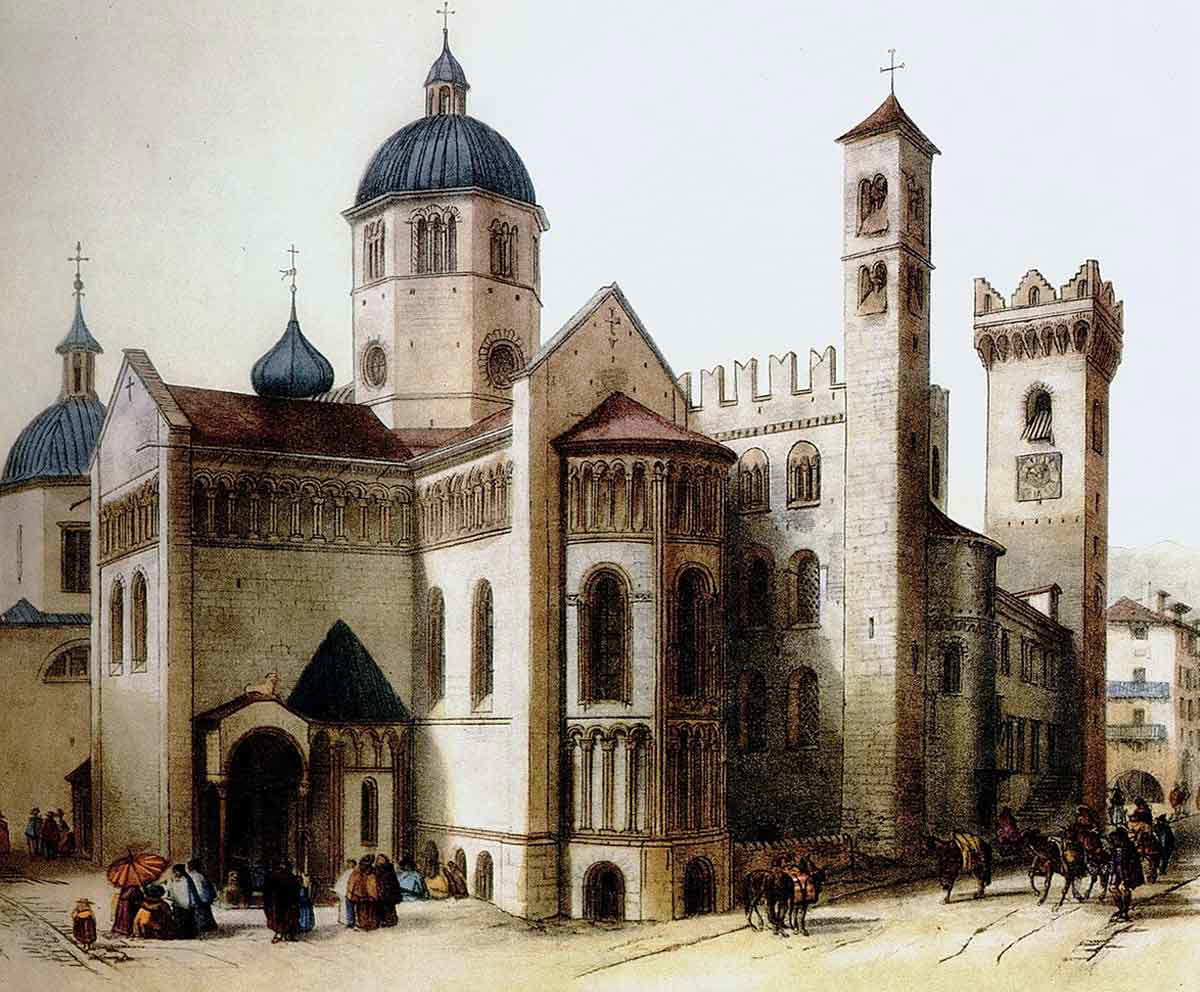

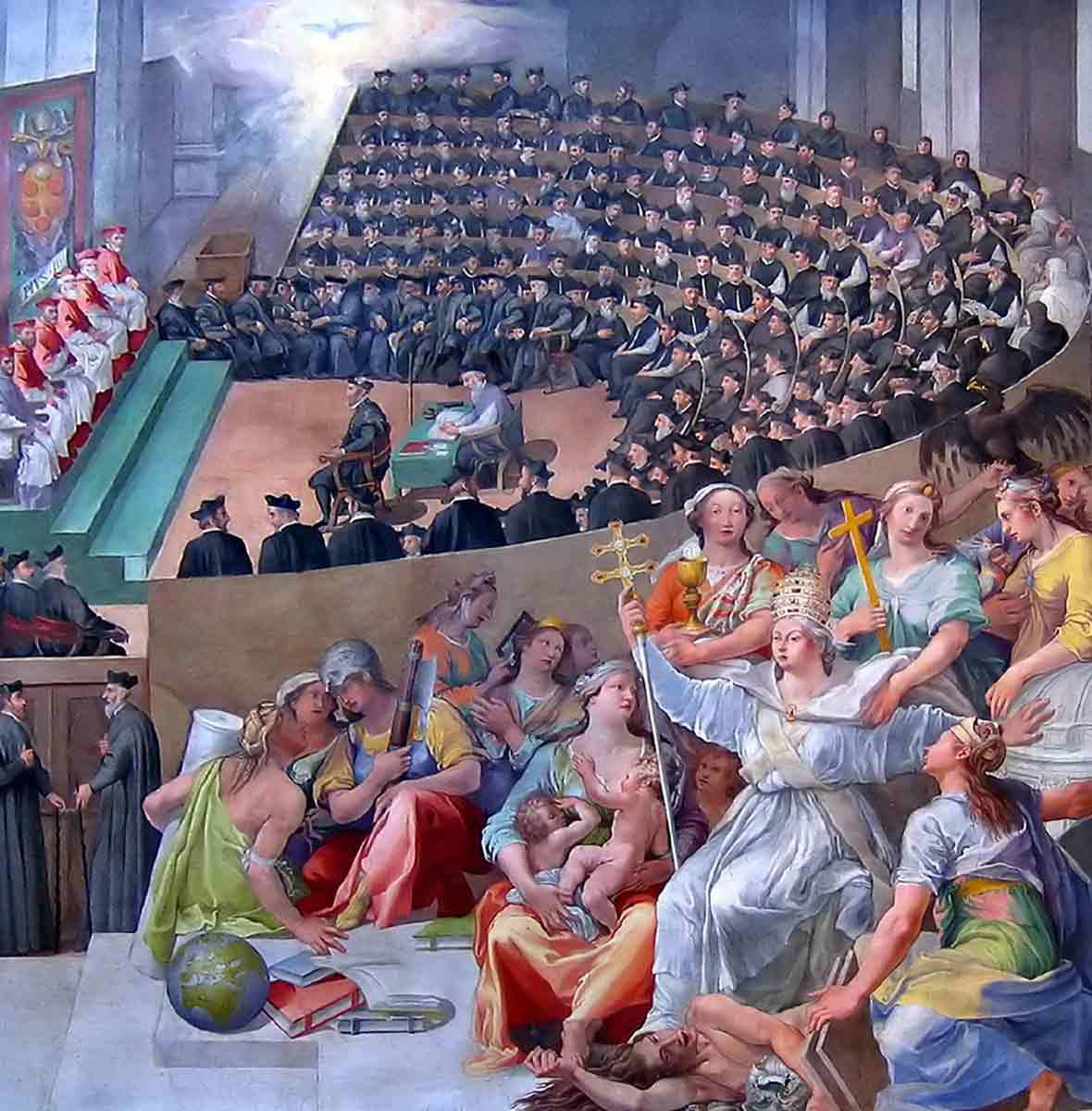

On December 13, 1545, around 30 bishops and other religious representatives gathered in the Cathedral of St. Vigilius in Trent, a town in northern Italy. It was the first session of the Council of Trent, the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Summoned by Pope Paul III after a 25-year waiting period, the Council of Trent was the Church’s response to the theological challenges of the Protestant Reformation and the calls for internal reforms. Despite bitter disputes, wars, an epidemic, and frequent interruptions, the Council of Trent managed to define the Catholic Church’s doctrine, inaugurating the so-called Counter-Reformation.

The Protestant Reformation and the Council of Trent

On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther is said to have nailed his Ninety-Five Theses on the front door of the Schlosskirche (Castle Church) in Wittenberg. The German priest had written his theses to protest against the Catholic Church’s widespread practice of selling indulgences to believers to grant them remission of their sins and thus shorten their stay in Purgatory. In particular, Luther sought to condemn Dominican friar Johann Tetzel’s unrestricted sale of indulgences with the sole purpose of repairing St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

“Since the pope’s income today is larger than that of the wealthiest of wealthy men, why does he not build this one church of St. Peter with his own money, rather than with the money of his indigent believers?” asked Luther in his theses. He was not the first Catholic to criticize the spiritual bankruptcy of the Roman papacy.

In the Renaissance period, the luxurious lifestyle and material wealth of many popes and clergy had led many to call for a sweeping reform of the Catholic Church. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Girolamo Savonarola, Pico della Mirandola, and Erasmus of Rotterdam, among others, denounced the abuses of the clergy and the popes, who ruled the Papal States as temporal kings rather than spiritual leaders. Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, for example, owned at least 79 pairs of gloves in his luxurious wardrobe.

Over the following years, Luther developed a new understanding of the Christian scriptures, which eventually turned into a religious revolution known as the Reformation, which challenged the very foundations of the Catholic Church’s theological structure. Discarding the system of indulgences, Luther declared that only faith and God’s grace could grant redemption and salvation. Known as sola fide (faith alone), the new doctrine threatened the existence of the Catholic Church and its role as a mediator between God and humankind.

In 1521, Luther was excommunicated after rejecting Pope Leo X’s request to recant his theses by burning the papal bull. As tensions between the Catholic Church and Luther’s supporters rose, many, including Emperor Charles V, called for an ecumenic council to mend the rift dividing the Christian world.

A 25-Year Prelude

In 1523, the new pope, Adrian VI, sent a document promising to reform the Catholic Church to the German princes gathered at the Diet of Nuremberg. The princes responded by requesting a “free Christian council on German lands.” Alarmed by the worsening political and military situation, Emperor Charles V also appealed to the pope to summon an ecumenic council to address the theological controversies.

However, Pope Clement VII, who succeeded Adrian VI in 1523, was reluctant to answer the numerous requests for a universal gathering. The pope’s hesitation stemmed from the antagonistic relationship between the papacy and previous councils. Indeed, in 1414, during the Great Western Schism, when two—and then three—popes struggled for control, the Council of Constance deposed them and elected a new pope.

Since the 12th century, some Christian canonists and philosophers had regarded a general assembly as a means to limit papal power. Known as Conciliarism, the theory that a general council held greater authority was formulated during the Council of Basel (1432-1438). In 1438, the conciliar ideas also informed the Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges, a decree issued by the king of France restricting papal jurisdiction.

In the 1520s, Clement VII was determined to avoid a conciliarist revival and limit the temporal rulers’ intervention in the Catholic Church’s affairs. A series of conflicts between King Francis I of France and Charles V further delayed the possibility of calling a new council. Meanwhile, in 1530, the Protestants presented their profession of faith at the Diet of Augsburg. In the following years, negotiation attempts between the two factions failed.

In 1536, the election of Pope Paul III, an advocate for internal reform, sparked new hopes. Tentatively, Paul III began laying the groundwork for a new council. In May 1542, he officially summoned the assembly in Trent. However, a new war between Francis I and Charles V delayed its opening. Finally, in November 1544, the pope issued a bull announcing the beginning of the general assembly. About a year later, the Council of Trent held its first session.

Council of Trent: The First Period (1545-1547)

In the 1542 Bull of Convocation (Initio nostro), Paul III presented the upcoming council as an opportunity “to ponder, discuss, execute and bring speedily and happily to the desired result whatever things pertain to the purity and truth of the Christian religion, to the restoration of what is good and the correction of bad morals, to the peace, unity and harmony of Christians among themselves.” The pope’s expectations, however, were far too optimistic. Indeed, the council dragged on, slowed by theological debates and wars, for 18 years. Theologian Paolo Sarpi described it as “the Iliad of our age.”

In the first sessions, the council debated the most pressing doctrinal issues challenged by the Reformation: original sin, justification, and the role of traditions. Rejecting Luther’s doctrine of sola fide, the assembly asserted the crucial role played by deeds and the observance of God’s commandments to achieve justification, or the state of grace, before God.

In the fourth meeting, the council members also condemned the Protestants’ claim that the Bible is the ultimate authority in matters of faith as heresy. Traditions that “have been transmitted in some sense from generation to generation down to our times” were just as crucial, the council asserted. Similarly, the bishops and legates discarded Luther’s emphasis on the need to return to the Hebrew and Greek versions of the Bible. On the contrary, they reiterated the authenticity of the Vulgate, the Latin translation of the text.

The Second Period (1551-1552)

In March 1547, as the troops of the Schmalkaldic League (an alliance formed by the Protestants of the Holy Roman Empire) neared the Alps and an epidemic of typhus broke out, the majority of the council voted a proposition to transfer the proceedings to Bologna. The 14 bishops representing Charles V protested the decision. While Trent was located within the borders of the Holy Roman Empire (albeit on the Italian side of the Alps), Bologna fell under papal hegemony.

When the council’s sessions resumed in the new location in April 1547, the emperor’s representatives refused to attend. Then, in February 1548, as Paul III denied Charles V’s request to move the council back to Trent, he suspended the proceedings.

In November 1550, the new pope, Julius III, agreed to resume the assembly in Trent. The sessions of the second period began in 1551. For the first and last time, a group of theologians and representatives from the Protestant territories traveled to the Italian town to participate in the proceedings. However, when the council rejected their request for revisions and demanded their submission, they left.

While the renewal of hostilities between Charles V and the German princes interrupted the council after a year, the bishops and legates in Bologna managed to issue decrees concerning the doctrine of penance, Extreme Unction (the anointing of the sick), and the Eucharist.

The Third Period (1562-1563)

After the 1552 session, the Council of Trent remained suspended for ten years. Paul IV, the successor of Paul III, was a firm advocate of papal supremacy. His extreme political and religious measures opened a period of unrest in Europe. Instead of reopening the council, Paul IV elected to launch a series of reforms through papal commissions in Rome. Their work, however, was thwarted by the papacy’s hostilities with Spain.

The Council of Trent resumed only in 1562, when Pius IV, alarmed by the spreading of Calvinism in France, decided to reopen the proceedings. During the new sessions, the council issued some of the most important reform provisions, including the obligations for bishops to reside in their dioceses and the establishment of seminaries to train future priests. In the past, the clergy’s negligence toward their preaching and spiritual duties were the most glaring examples of the abuses and moral bankruptcy of the Church. Lecherous priests and greedy monks were staples in the satirical works of Boccaccio and Chaucer.

In the remaining sessions, the council also laid down specific liturgical instructions regarding the mass. Additionally, it addressed the topic of Purgatory and the veneration of saints and images, a practice opposed by the Protestants. In November 1563, a decree on marriage affirmed its indissolubility, proclaiming its sacramental nature.

The Legacy of the Council of Trent

The last session of the Council of Trent took place between December 3 and 5, 1563. The following year, with the bull Benedictus Deus, the pope formally ratified the decrees issued in Trent. At the same time, he made papal approval a prerequisite for any future interpretation of doctrinal matters, prohibiting the publication of unauthorized commentaries on the provisions of the Council of Trent. A special committee, the Sacred Congregation of the Council, was tasked with issuing the correct understanding of all decrees.

In November 1564, Pius IV summarized the dogmas and doctrinal principles set in Trent in the Professio fidei Tridentina (Tridentine profession of faith). It was the beginning of the so-called Counter-Reformation. Over the following years, with the publication of the Tridentine Index of Forbidden Books and the Catechism of Trent, the papacy reasserted its role as the sole source of authority in matters of faith.

Strengthened by the internal reforms issued by the council, the Catholic Church also launched a propagandistic campaign to revive the believers’ devotion. Baroque art and liturgical music, full of eye-catching effects and splendor, played a crucial role in reaffirming the Church’s position. Through its educational programs and schools, the Jesuit order was also a leading agent in spreading the “Tridentine doctrine.”

While the Council of Trent successfully inaugurated a period of spiritual renewal, it failed to mend the split between Catholics and Protestants. In his The Historie of the Council of Trent (1620), Paolo Sarpi affirmed that the council worsened the divisions within the Christian world, making “the parts so obstinate, that the discords are become irreconcilable.” Indeed, when Sarpi wrote his treatise, tensions between the two factions had already led to a series of bloody religious wars.